What is Molecular Biology?

The field of molecular biology studies macromolecules and macromolecular mechanisms found in biology, such as the molecular properties of genes and the mechanisms of gene duplication, mutation and expression.

Given the fundamental importance of these macromolecular mechanisms throughout the history of molecular biology, philosophical attention to the concept of mechanisms can most clearly describe the history, concepts, and case studies used by philosophers of molecular biology.

Some clinical research and medical treatments caused by molecular biology belong to gene therapy, and the application of molecular biology or molecular cell biology in medicine is now called molecular medicine. Molecular biology also plays an important role in understanding the formation, function and regulation of various parts of cells, and can be used to effectively target new drugs, diagnose diseases and understand cell physiology.

1. History of Molecular Biology

1.1 Origins

The field of molecular biology originated from the fusion of geneticists, physicists, and structural chemists on a common problem: the nature of heredity. In the early 20th century, although the nascent field of genetics was guided by the laws of Mendelian separation and independent classification, the actual mechanisms of gene reproduction, mutation, and expression remained unknown. Thomas Hunt Morgan and his colleagues used the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism to study the relationship between genes and chromosomes in the genetic process (Morgan 1926; Darden 1991 discussion; Darden and Maull 1977; Kohler 1994; Roll-Hanson 1978; Wimsatt 1992 ). Hermann J. Muller, a former student of Morgan, recognized that "genes are the foundation of life" and therefore set out to study its structure (Muller 1926). Muller discovered the mutagenic effects of X-rays on fruit flies and used this phenomenon as a tool to explore the size and nature of genes (Carlson 1966, 1971, 1981, 2011; Crow 1992; Muller 1927). But despite the power of mutagenesis, Mueller recognized that as a geneticist, his ability to explain the more basic characteristics of genes and their roles is limited.

1.2 Classical Period

The classic period of molecular biology began in 1953, when James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the double helix structure of DNA (Watson and Crick 1953a,b). The scientific relationship between Watson and Crick unifies the various disciplinary methods discussed above: Watson, Luria, and the students of the phage group recognized the need to use crystallography to clarify the structure of DNA; Crick, a Schrodinger's "What is Life?" Turned to biology, received training in the theory of X-ray crystallography and made contributions. At the University of Cambridge, Watson and Crick discovered that they were interested in both genes and DNA structure (see Science Revolution entry).1.3 Going Molecular

The molecular biologist Sydney Brenner in a letter to Max Perutz in 1963 heralded the next intellectual migration in molecular biology:

It is now generally recognized that almost all "classical" problems in molecular biology have either been solved or will be solved in the next ten years... Because of this, I always feel that the future of molecular biology lies in extending research to other aspects of biology. Areas, especially development and nervous system. (Brenner, Letter to Perutz, 1963)

Therefore, this "going to the molecule" process is usually equivalent to using the experimental methods of molecular biology to examine complex phenomena (whether it is gene regulation, behavior or evolution) at the molecular level. The molecularization of many fields has introduced a series of questions of interest to philosophers. Inferences about the study of model organisms such as worms and flies raise questions about extrapolation. The reduction technology of molecular biology raises the question of whether scientific investigations should always strive to reduce to lower and lower levels.

1.4 Going Genomic and Post-Genomic

In the 1970s, as many leading molecular biologists migrated to other fields, molecular biology itself was also moving towards genomics (see genomics and post-genomics entries). The genome is the collection of nucleic acid base pairs in the cells of an organism (adenine (A) is paired with thymine (T), and cytosine (C) is paired with guanine (G)). The number of base pairs varies from species to species. For example, the Haemophilus influenzae (the first bacterial genome sequenced) that caused the infection has approximately 1.9 million base pairs in its genome (Fleischmann et al., 1995), while the Homo sapiens that caused the infection is in its genome. Carrying more than 3 billion base pairs. Its genome (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2001, Venter et al., 2001). The history of genomics is the history of developing and using new experimental and computational methods to generate, store, and interpret such sequence data (Ankeny 2003; Stevens 2013).

The development of genomics and post-genomics has raised many philosophical questions about molecular biology. Since the genome requires a large number of other mechanisms to promote the production of protein products, can DNA really prioritize causally? Similarly, in the face of such interdependent mechanisms involving transcription, regulation, and expression, can DNA alone serve as the carrier of genetic information, or can the information be distributed among all these entities and activities? Is it appropriate to infer the way the human genome works from the genome information of other species?

2. Relationship to other biological sciences

- Molecular biology is the study of the molecular basis of biological phenomena, focusing on molecular synthesis, modification, mechanism and interaction.

- Biochemistry is the study of chemical substances and important processes that occur in organisms. Biochemists are very concerned about the role, function and structure of biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and nucleic acids. Biochemistry usually focuses more on molecules other than proteins. It also focuses on the chemical effects that occur in the presence of nucleic acids and a large number of substances, such as the effects of venom. In addition, biochemistry uses many methods based on organic chemistry research.

- Genetics is the study of how genetic differences affect organisms. Genetics attempts to predict how mutations, individual genes, and genetic interactions affect the expression of phenotypes. Genetics pays particular attention to genetic traits and how changes in the genetic code affect organisms. This focus on heritability means that genetics is usually best studied at the population level, making it a larger field than molecular biology.

Each of these three areas overlaps and affects other areas. In particular, genetics and molecular biology have a lot in common, especially in the role of RNA. RNA can not only store information like DNA, but also perform active functions like protein.

3. Laboratory Methods

3.1 Molecular cloning

One of the most basic techniques of molecular biology to study protein functions is molecular cloning. In this technology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and/or restriction enzymes are used to clone the DNA encoding the target protein into a plasmid (expression vector). The vector has 3 distinctive features: an origin of replication, a multiple cloning site (MCS), and a selection marker that is usually antibiotic resistance. Located upstream of the multiple cloning site are the promoter region that regulates the expression of the cloned gene and the transcription initiation site. The plasmid can be inserted into bacteria or animal cells. The introduction of DNA into bacterial cells can be accomplished by uptake of naked DNA for transformation, cell-cell contact for conjugation, or viral vector transduction. The introduction of DNA into eukaryotic cells, such as animal cells, by physical or chemical methods is called transfection. There are several different transfection techniques available, such as calcium phosphate transfection, electroporation, microinjection, and lipofection. The plasmid can be integrated into the genome, resulting in stable transfection, or it can remain independent of the genome, which is called transient transfection.

The DNA encoding the protein of interest is now in the cell and the protein can now be expressed. Various systems, such as inducible promoters and specific cell signaling factors, can be used to help express the protein of interest at high levels. Large amounts of protein can then be extracted from bacteria or eukaryotic cells. The enzyme activity of the protein can be tested under various conditions, the protein can be crystallized to study its tertiary structure, or in the pharmaceutical industry, the activity of a new drug on the protein can be studied.

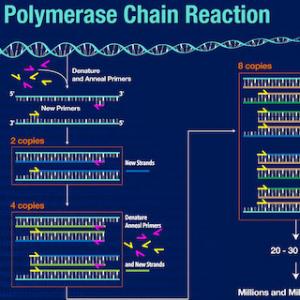

3.2 Polymerase chain reaction

3.3 Gel electrophoresis

2% agarose gel in borate buffer cast in a gel tray.Gel electrophoresis is one of the main tools of molecular biology. The basic principle is that DNA, RNA and protein can all be separated by electric field and size. In agarose gel electrophoresis, DNA and RNA can be separated by a charged agarose gel according to their size. You can use SDS-PAGE gels to separate proteins based on size, or use so-called 2D gel electrophoresis to separate proteins based on size and charge.

3.4 Macromolecular imprinting and detection

The terms northern blot, western blot, and eastern blot originate from a joke that was originally a molecular biology, which was used after Edwin Southern described the technique for blotting DNA hybridization. Patricia Thomas, the developer of Northern Blots, later called Northern Blots, and did not actually use this term.3.5 Microarray

A DNA microarray is a collection of dots attached to a solid support (such as a microscope slide), where each dot contains one or more single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide fragments. The array can place a large number of very small (100 micron diameter) spots on a single slide. Each point has a DNA fragment molecule complementary to a single DNA sequence. A variant of this technique allows the gene expression of an organism at a specific developmental stage to be limited (expression profile). In this technique, the RNA in the tissue is separated and converted into labeled complementary DNA (cDNA). The cDNA is then hybridized with the fragments on the array, and the visualization of the hybridization can be completed. Since multiple arrays can be made using exactly the same fragment positions, they are particularly useful for comparing the gene expression of two different tissues, such as healthy tissues and cancerous tissues. In addition, one can measure which genes are expressed and how that expression changes over time or other factors. There are many different methods to fabricate microarrays; the most common are silicon chips, microscope slides with ~100 micron diameter spots, custom arrays, and arrays with larger spots on porous membranes (macro arrays). There can be from 100 points to more than 10,000 points on a given array. Arrays can also be made of molecules other than DNA.3.6 Allele-specific oligonucleotides

Allele-specific oligonucleotides (ASO) are a technique that can detect single-base mutations without the need for PCR or gel electrophoresis. Short (20-25 nucleotides in length) labeled probes are exposed to non-fragmented target DNA. Due to the short length of the probe, the specificity of hybridization is very high. Even a single base change will hinder hybridization. . Then the target DNA is washed to remove unhybridized labeled probes. Then analyze whether there is a probe in the target DNA by radioactivity or fluorescence. In this experiment, as with most molecular biology techniques, controls must be used to ensure the success of the experiment.In molecular biology, procedures and techniques continue to evolve, and old techniques are abandoned. For example, before the advent of DNA gel electrophoresis (agarose or polyacrylamide), the size of DNA molecules was usually determined by the velocity sedimentation in a sucrose gradient. This is a slow and labor-intensive technique that requires expensive equipment; Before the sucrose gradient, viscometry was used. In addition to their historical interest, it is often worthwhile to understand the old technology, because sometimes it is useful to solve another new problem for which the new technology is not suitable.

4. Further reading

- Cohen SN, Chang AC, Boyer HW, Helling RB (November 1973). "Construction of biologically functional bacterial plasmids in vitro". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 70 (11): 3240–4. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.3240C. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.11.3240. PMC 427208. PMID 4594039.

- Rodgers M (June 1975). "The Pandora's box congress". Rolling Stone. 189: 37–77.

- Roberts K, Raff M, Alberts B, Walter P, Lewis J, Johnson A (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.